Nepali Migrant Workers Risk Their Lives in Europe

Yam Kumari Kandel

KATHMANDU, NEPAL — On Dec. 4, 2024, Tek Bahadur B.K. received a call from Greece informing him that his brother, Ganesh B.K., had died that morning. A few days later, the family huddled together in Kathmandu, waiting for a coffin that would never arrive. Though Nepal’s government approved funds for repatriation, the family found through official correspondence that Greek authorities had already buried Ganesh B.K. The Nepali government is still investigating both the cause of death and why his body was buried without family notification.

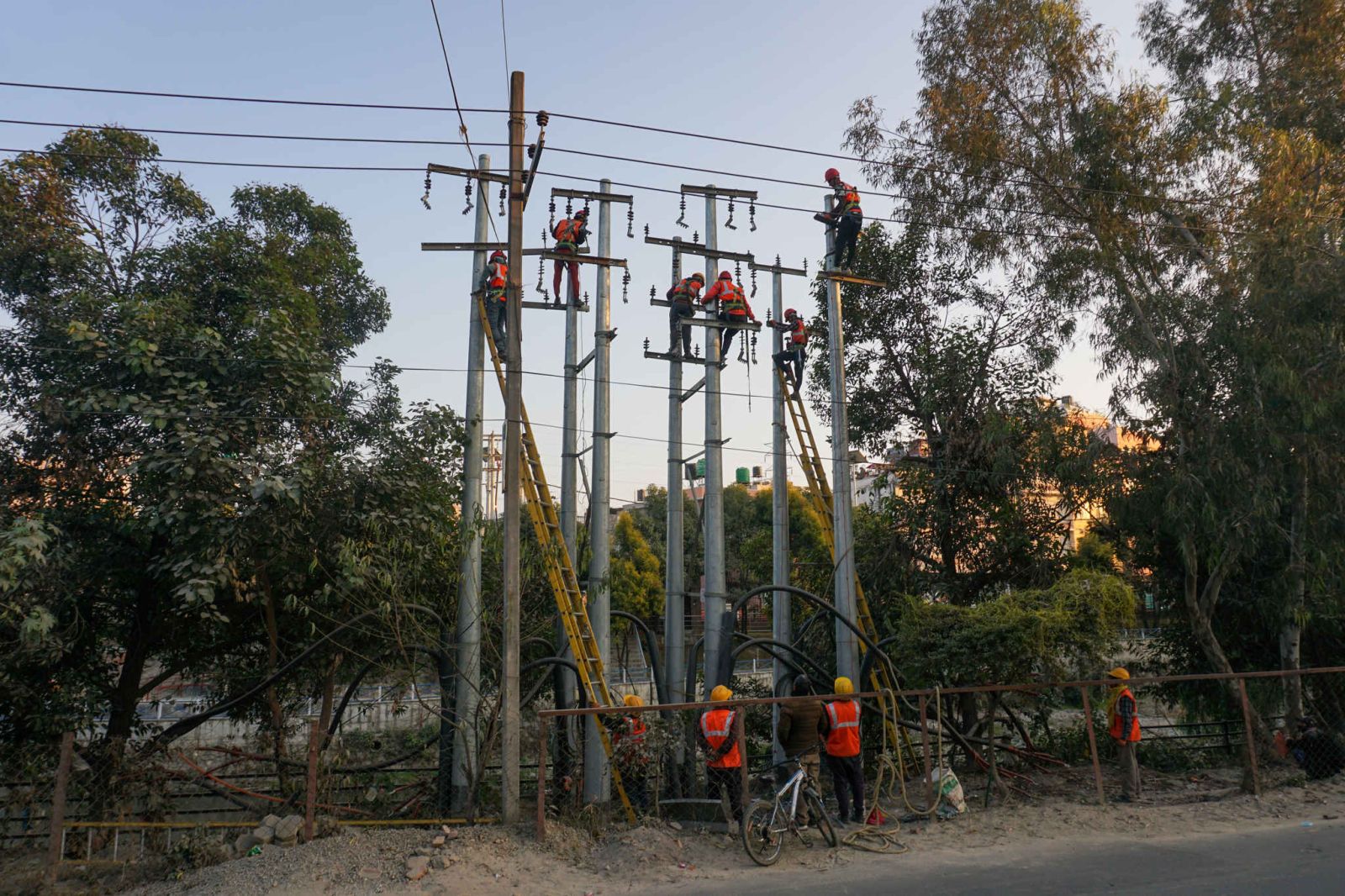

Persian Gulf countries were once the gold standard for jobs for Nepalis looking to earn money abroad, despite widespread accounts of worker abuse. That region still attracts scores of Nepali workers, but Europe’s promise of stronger worker protections lures people like Ganesh B.K. to countries there — Greece, Romania, Croatia, Malta, Poland and others. As citizens of those countries increasingly head to central and western Europe for work, demand for labor in the places they’ve left behind has increased. The type of work varies. Ganesh B.K. worked on a farm.

But while dreams of European jobs surge in Nepal, some private recruitment companies, colloquially called manpower agencies, play a dangerous game: forging paperwork and charging would-be migrant workers exorbitant rates to circumvent foreign hiring government quotas.

Then, agencies create an elaborate fiction where workers, most of them from rural Nepal with no experience in the world beyond, appear to have found jobs on their own — a prerequisite for getting an individual permit, says Shanti Kumari Singh, rescue and repatriation officer at the Secretariat of Foreign Employment Board, a government organization.

Workers who pay dishonest agencies for individual permits wind up having no protections, even in the worst cases.

Every day for the last five years or so, Singh says at least two desperate families come to the board seeking help. Between just mid-October 2024 and early January this year, 17 workers who went to Europe on individual permits died, she says.

With no paper trail linking back to the agencies that likely sent them abroad in the first place, most families must shoulder the burden of repatriation alone.

Nepal has a long history of labor migration. Manpower agencies emerged in the mid-1980s when Nepal’s government first tried to harness this human tide, creating rules for workers venturing beyond South Asia. What began with handfuls of people seeking fortune abroad has swelled into an economic lifeline. In 2023, over 2 million Nepali workers scattered across the globe sent home a staggering US$11 billion, pumping more money into their homeland than all foreign aid and investment combined. These remittances now make up more than a quarter of Nepal’s gross domestic product.

Nepali workers can migrate through two legal channels: with individual permits by securing jobs on their own, or on institutional permits through one of Nepal’s 1,026 registered manpower agencies. Both routes demand a maze of paperwork — proof of employment, salary details and benefits, all meticulously documented. While most choose the well-worn manpower agency path, complete with official “master IDs” tracking their journey through Nepal’s bureaucracy, some who are either skilled, educated or aware of the international market opt for individual labor permits. Those permits are issued by Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment.

Institutional work permits for Europe are both scarce and costly, says Guru Datta Subedi, information officer at Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment.

Individual permits — the ones most Nepali workers tend to travel on — are more freely to be had.

As the number of Nepali workers migrating independently to Europe increases, so do the number of deaths abroad, says Subedi. Overall, the number of Nepali migrants who died while abroad rose from 672 in 2019-2020 to 1,346 in 2023-2024.

Ganesh B.K.’s journey began with a loan and a promise. In March 2024, he borrowed 800,000 Nepali rupees (US$5,774) — a fortune for many Nepalis — because a recruiter promised him that he could earn 115,000 rupees (US$830) a month in Serbia. He traveled on an individual permit.

Ganesh B.K. worked as a cashier in Serbia but didn’t receive the salary he was promised, so he moved illegally to Greece. From there, he was able to send up to 100,000 rupees (US$721) each month to his family.

He left no paper trail explaining his choice, but his moves follow a familiar pattern: Workers gamble their lives on shortcuts engineered by unscrupulous agencies, legal protections vanish, and recruiters dodge accountability.

There are more destinations — 188 countries — where Nepali workers can travel on individual permits than the 111 where they can travel through manpower agencies on institutional permits. The number of Nepalis traveling on new individual permits is skyrocketing, from 5,317 people in 2020-2021 to 95,038 in 2023-2024. While the Gulf continues to be the most popular destination, according to data collated by Global Press Journal, European destinations saw a significant jump, from 4,129 to 21,260.

Govinda Prasad Humagai, director of the complaints and cases branch of the Department of Foreign Employment, says his office received just over 2,000 complaints between August 2024 and early January this year from workers who obtained individual labor permits for different countries around the world, but were cheated out of promised salaries and benefits. While the department can raid and prosecute agencies if workers provide evidence of illegal recruitment, enforcement is challenging. Because workers technically apply using their own name and IDs rather than through manpower agencies, if things go wrong, the paperwork shows only eager individuals chasing opportunities, never the agencies who sold them a mirage.

Singh works with embassies daily to repatriate bodies but says many families don’t even know how to approach her office, or even where the office is located.

The situation leaves legitimate manpower agencies at a disadvantage.

“Our reputation has been tarnished,” says Meghnath Bhurtel, general secretary of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies.

He says it is only “brokers, middlemen and human traffickers” who send people illegally. Real agencies can’t send workers to most of Europe because Nepal and those countries haven’t reached agreements to let that happen, he says.

Ganesh B.K. left behind a 21-year-old wife and an 8-month-old baby. His family has requested the secretariat to at least send them his mobile phone and photos of his funeral, but they have yet to receive anything.

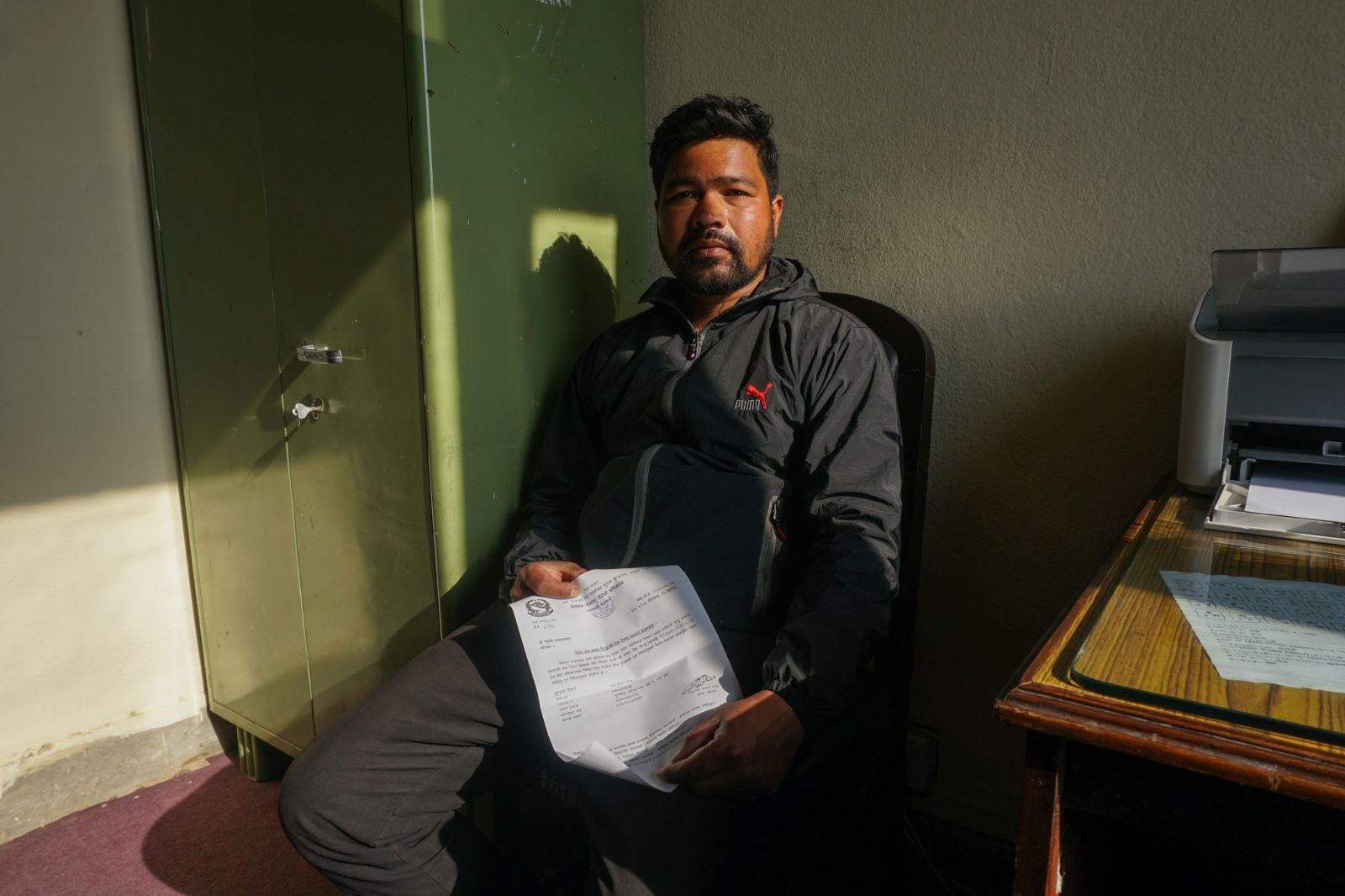

His brother, Tek Bahadur B.K., says the family could not even perform his last rites at Pashupatinath’s Aryaghat, one the largest cremation areas in Nepal — one hope they had when they received the call that cold December evening.

“I begged him to stay in Nepal,” recalls Tek Bahadur B.K., who wasn’t sure working abroad was safe. “Now look what happened. We couldn’t even see his body one last time.”

Photo credit: Yam Kumari Kandel/Global Press Journal.